JUNE IS BUSTIN’ OUT ALL OVER! (with apologies to Rodgers and Hammerstein)

A brief look at historic wedding dresses.

June is often regarded as the month for weddings – and given our pandemic era lives of the past year, many weddings, once postponed, are being rescheduled. For this post, we thought it appropriate to highlight some wedding traditions and objects from the Costume Collection.

Prior to the mid 19th c. women, a well as men, would simply wear either a new garment, or their ‘best’ garment for their nuptials. In the 18th c., a gown worn for a wedding could be richly embroidered or woven with silver threads, which would softly glow under candlelight. Gowns of white fabric were common and fashionable in the early 19th c., as this fashion plate from “Ackermann’s Repository” from June, 1816 attests to. There is nothing, aside from the caption, which signals to us that this is a ‘wedding dress.’ There is no presence of a veil, the telltale clue to many wedding fashions seen in fashion plates.

Ackermann’s Repository, 1816, Private Collection. Hand colored plate.

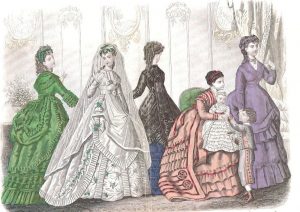

Wedding dresses follow contemporary fashion styles and mores. Fashion publications from the 1840s onward illustrated wedding dresses which were distinguished by the wearing of a veil or the addition of orange blossoms to the ensemble. However, their style of dress followed that of contemporary fashion.

Though a white gown is associated today with wedding attire, that was not always the case. Queen Victoria, at her wedding to Prince Albert in February of 1840, wore white and is often credited with starting the trend. Victoria also wore a wreath of orange blossoms in her hair, a tradition that would continue throughout the 19th c. in which orange blossoms were worn as part of a wedding ensemble. Queen Victoria’s eldest daughter, Princess Victoria, wore orange blossoms on her dress for her wedding in 1858 and many brides copied this motif and decorated their gowns with approximations of the flowers. In lieu of fresh blossoms, wax replicas were used, and some of these wax replicas survive today. Though the orange blossom originated in China, it was later grown in the West, and associated not only with its pleasant scent, but also its symbolic link to fertility and virtue.

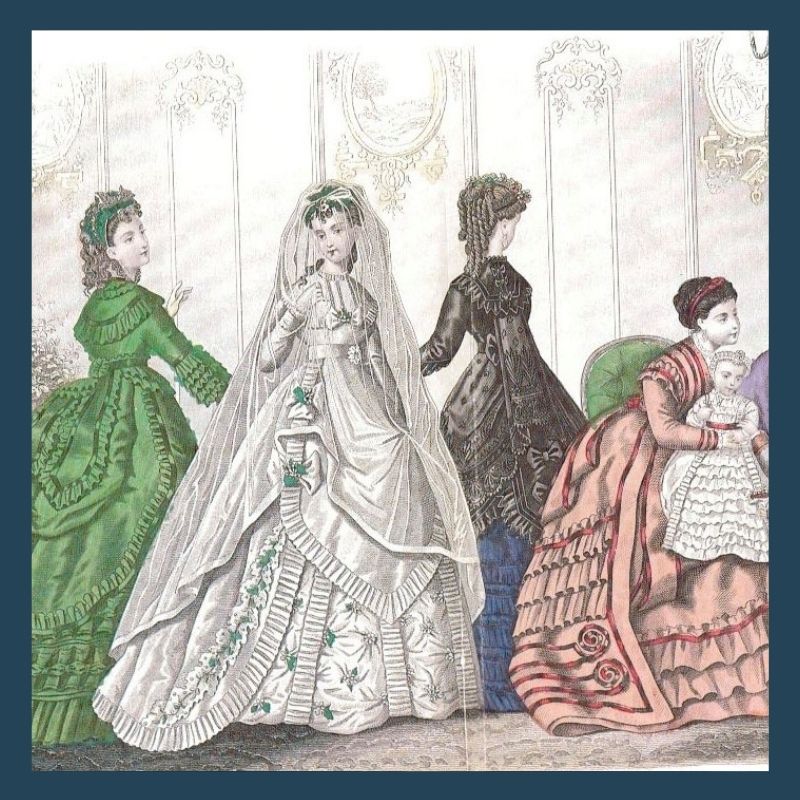

Godey’s Lady’s Book, 1869. Note the presence of the orange blossoms on the bride’s gown.

Edith Wharton, in “The Age of Innocence” notes that in New York society of the late 1870s a bride would re-wear her wedding gown at a later date to a society function. However, many women would merely wear either a new dress, or their best dress for their wedding, and that garment might not be white.

A wedding gown is one of the few artifacts of clothing that many women would save, as it represents an important life event. Although we have many wedding gowns in the costume collection, we have none that are associated with 19th c. weddings.

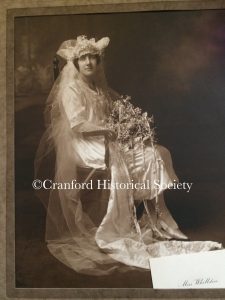

This wedding gown from the collection shows the bride, who wed in 1921- in the loose-fitting, shapeless silhouette of the early 1920s.

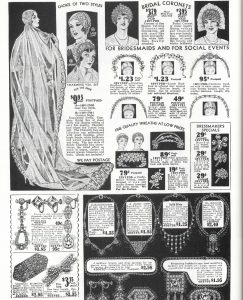

This page from a Franklin Simon catalog dated 1921 shows similar headpieces to those worn by this fashionable bride.

However, some of our 20th c. wedding gowns tell wonderful stories. Our next example is the wedding gown of Janet Peterson, who married her husband Carl in 1942 during World War II. Her gown was made by her mother. The groom wore his Army dress uniform; and the story that accompanied the donation was that Carl removed one of the buttons from his bride’s gown and carried it with him when he returned to the war. The late Mr. Carl Peterson was a President of the Historical Society.

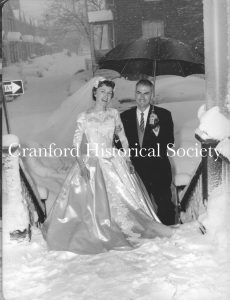

Another recent acquisition is the wedding ensemble of Mary Curtis, wife of our late trustee Bill Curtis. Objects tell stories, and this one has a wonderful one: there was a blizzard the day before their 1962 wedding, and everyone was snowed in. The wedding proceeded, with few people in attendance, but provided Bill with a story he loved to tell about his beloved Mary.

All of these examples follow the lines of fashion of the period in which they were worn.

Even in current times, some brides opt for ‘practicality, ‘ and some in the past had limited options due to shortages. Not every woman marries in a white dress, or even a gown. This recent piece from the New York Times showed wedding gowns from World War II made out of a rare and valued found object — a silk parachute. It draws parallels to Covid-era weddings, where in many shops and venues were closed, and many weddings postponed. The dress in this piece is from the collection of the National World War II Museum in New Orleans.

Another example of a dress made from parachute silk was recently gifted to the National Museum of American Jewish History, a branch of the Smithsonian in Philadelphia. If you scroll to page 6, you will see the story of this particular parachute gown.

And surely a sign of our modern times was this bride, who had her wedding downsized due to Covid. Scroll down this recent article to see Sarah Studley wearing her reception dress to celebrate something else – receiving her first Covid-19 vaccine! https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/03/style/wedding-dress-activism.html?referringSource=articleShare

If you are interested in wedding fashions, albeit from a Western perspective, check out “The Wedding Dress, 300 Years of Bridal Fashions” by Edwina Ehrman (Victoria and Albert Museum, 2014). The book has a primarily British perspective, but is a treasure trove of illustrations and information. Bear in mind that wedding dress, and traditions, are different across ethnicities and religions; but all celebrate the union of a two people.

And no, sadly, we in Cranford do not own a parachute silk gown …. but our other wedding gowns tell specific, and special, stories.

Article and photos submitted by Gail Alterman, Cranford Historical Society’s Costume Curator.

All images Copyright Cranford Historical Society.

Please do not use without permission.

Recent Comments