The following article written by Vic Bary, Cranford Historical Society Curator, tells about the 19th Amendment and the active role of some courageous Cranford women in support of women’s suffrage.

Photo above – Credit: The Library of Congress

—————

New Jersey Women Could Vote Before 1807

When I began my research, I was amazed to learn that New Jersey women initially could vote per their 1776 State constitution. That document stated that “all inhabitants of this colony, of full age, who are worth fifty pounds … and have resided within the county … for twelve months” are enfranchised to vote. It made no reference to gender or race. Lest you be too ready to stand up and shout “hallelujah”, you need to keep two things in mind. First, 50 British Pounds in 1776 were the equivalent of nearly $122,000 today. Second, only unmarried women and widows could hold property in their own names. Married women’s property redounded to their husbands. Accordingly, married women could not meet the 50 Pounds voting threshold. Thus, in 1776, the vote was available to only wealthy single women and wealthy widows.

In 1797 the New Jersey Constitution was revised to stipulate that voters had to be “free inhabitants”. In 1807, New Jersey again restricted enfranchisement, this time to “tax paying white male citizens” (italics added). Votes for women became ‘easy come, easy go’.

The Women’s Suffrage Movement Begins

Most historians date the Women’s Suffrage movement from the July 19-20, 1848 Seneca Falls event called by local Quaker Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Billed as the “Woman’s Rights Convention”, it attracted 239 women and one male – African American abolitionist Frederick Douglass.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton (Getty Images)

Of the eleven women’s rights resolutions presented for a vote, ten passed unanimously. The remaining resolution (#9) – demanding the right to vote for women – only barely passed after impassioned speeches by both Stanton and Douglass. Perhaps this was an early indication that the struggle for women’s suffrage would not be an easy one, taking another 72 years to realize.

Women’s Issues Other Than Suffrage

Most attendees of the Seneca Falls convention were also focused on additional issues important to women and seen as preventing their achieving full equality with men. Among those issues were men’s abuse of alcohol, which was seen as leading to the psychological and physical abuse of women and children by husbands/fathers, as well as wasting funds that should be devoted to rent and food. Many suffragists would also be members of the Temperance movement.

Opening greater education and employment opportunities to women, the full recognition of the rights and opportunities promised by Abolition, healthcare, and pure food and clean neighborhoods were among issues considered in need of immediate attention. When we later meet leading Cranford women involved in the suffrage movement, we will see their involvement with some or all of these issues.

Two Possible Paths to Suffrage

The path to suffrage could take either of two routes, and opposing suffrage groups would champion one route or the other.

The first route, favored by Lucy Stone’s National American Woman Suffrage Association, was to leave women’s suffrage up to the individual states. In 1869, Wyoming enfranchised women, followed next by Colorado (1893), Utah (1896) and Idaho (1896). These western states were so moved, at least in part, by their need to attract female residents for their overwhelmingly male populations.

Lucy Stone

In the early 20th Century, state enfranchisement of women was enacted by Washington (1910), California (1911), Oregon, Arizona and Kansas (1912), Alaska and Illinois (1913), North Dakota, Nebraska and Arkansas (1917), Michigan (1918), and Indiana (1919). Notably absent from this list were the presumptively liberal Northeastern “Blue” states. It wasn’t for their lack of trying.

The second path to enfranchisement, based on an amendment drafted by suffragists in 1878, and led by Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton of the National Woman Suffrage Association, was an amendment to the U.S. Constitution. This route required the amendment to be approved by both the Senate and the House, after which it would be sent on to the states for ratification. Seventy-five per cent (75%), or 36 of the 48 states, would have to approve the amendment in order for it to become law. Congress approved the amendment on June 4, 1919. It then went to the individual states for ratification.

Susan B. Anthony (NY Daily News)

With 35 state approvals in hand, the amendment went before the Tennessee legislature in August, 1920 for approval. All of the remaining 12 states had either rejected the amendment or refused to consider it. Tennessee ratified it, but had it not, the 19th Amendment would have failed to be adopted. Passage was that close a thing.

Onward Towards Suffrage

Suffrage took somewhat of a back seat during the Civil War and early days of Reconstruction, but then thrust itself into the national conscience once again. In 1872. Susan B. Anthony was tried and convicted of illegally voting in a Presidential election. She was not the only suffragist to crash the polls. At the 1886 dedication ceremonies for the Statue of Liberty, the New York headquartered National Association of Suffragists hired a barge and crashed the proceedings with a large banner reading “American Women Have No Liberty”.

In early 1910, the Cranford Chronicle reported that a woman’s suffrage club had been formed, with university approval, at the University of Pennsylvania. Two years later, Theodore Roosevelt’s Progressive Party made women’s suffrage a plank on their ticket and supported a Constitutional amendment

In 1915, Dr. Anna Howard Shaw’s gift automobile – “Eastern Victory” – was seized by authorities for non-payment of taxes. Dr. Shaw stated that, since she was denied the vote, this represented “taxation without representation – the ballot and taxes go hand in hand.”

All Was Not Peaches and Cream

While there was an active and vocal woman’s suffrage movement, there was an equally, and initially more successful, Anti-Suffrage movement. Among the most visible and outspoken opponents of suffrage were former President Grover Cleveland and his wife. Many church leaders also actively opposed suffrage.

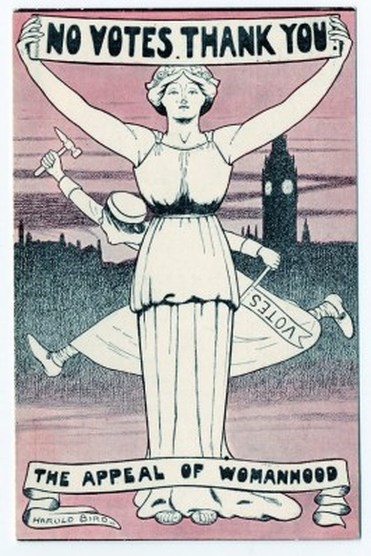

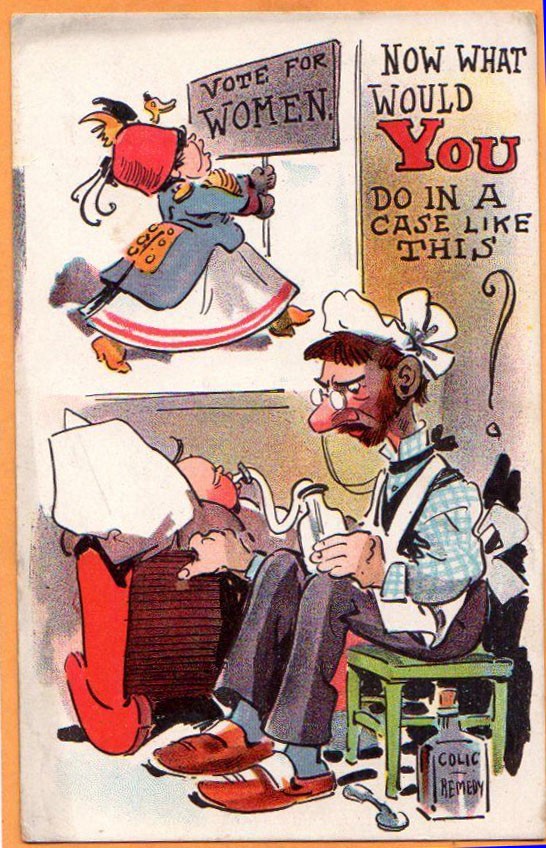

In 1906 the Philadelphia Record reported “A recent statistical investigation of club women towards suffrage revealed that a large proportion of them are either anti-suffragists, or indifferent to it.” Other newspapers and periodicals reported wide-spread indifference to suffrage among women. (Note the opposing caricatures of Indifferent and Pro-Suffrage Woman in the poster, below.)

This was the more genteel side of opposition. More strident opposition posited that suffrage would lead to the destruction of the home and the neutering of men. Husbands and children would be neglected and the very fabric of civilization would be torn asunder.

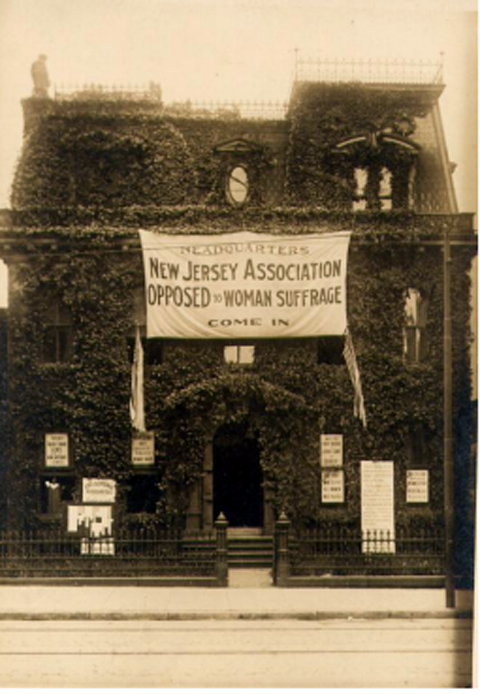

Suffragists were often accused of loose morals or homosexual leanings, ugliness and outright insanity. The following photograph of the New Jersey Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage headquarters in Trenton strikes me as unconsciously capturing the very darkness and ivy-encrusted nature of their beliefs.

HQ – NJ Assn. Opposed to Woman Suffrage

And anti-suffragists were not without success. In 1915, when suffrage was put on the ballot in Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York and Pennsylvania, it was roundly defeated in each state. (It won in 1917 in New York). Needless to say, only males were able to vote in these elections.

Things took their darkest turn in October, 1917 when The National Women’s Party, founded by New Jersey Quaker Alice Paul, took a page from England’s Mrs. Pankhurst’s in-your-face style of protest and actively picketed the White House, burning President Wilson in effigy. The picketers activities were considered anti-patriotic and seditious as the country was at war. They were roughly arrested, and when they refused to pay their modest fines in spite of the judge’s pleading with them to do so, they were sent to a dismal workhouse for imprisonment. When they went on hungers strikes there, they were force fed.

Alice Paul

Meanwhile in Cranford

Cranford had no local newspapers to report on Suffrage happenings until the 1890s (Cranford Chronicle starting in 1894 and The Cranford Citizen starting in 1898). The November 6, 1896 Cranford Chronicle drew attention to the forthcoming debate between a Mrs. Greene (presumably for Suffrage) and a Mr. Whitehead (presumably against Suffrage). Where and when exactly this debate was to take place was not identified in the article.

Other than the 1896 Greene versus Whitehead debate article, local reporting on Suffrage didn’t begin until 1902, and for the first ten plus years concerned events in England and Europe and then in states other than New Jersey. But, in the January 22, 1914 issue of The Cranford Citizen, a new column entitled Suffrage Notes appeared. It reported that the 100 tickets for the Suffrage Bridge (to be held at Fannie Bates’ Hampton Hall) were selling rapidly. A Suffrage Tea would be held the following month at the home of Mrs. Townsend, and that the bulletin of the National American Woman Suffrage Association reported on a talk given by Dr. Shaw (she whose automobile would be seized the following year for non-payment of taxes). The column would continue to report on local and area suffrage activities in a straight forward manner, free of editorial comment or disparagement.

The column appeared regularly after that, proudly declaring in the October 7, 1915 issue “New Jersey Next” (to enfranchise women), only to have to acknowledge two weeks later that the vote had failed in every county.

In late October/early November, 1916, both The Cranford Citizen and the Cranford Chronicle reported that the Cranford Equal Suffrage League had leased the Cranford Theater to show the pro-suffrage movie “The Fall of a Nation”.

Cranford Suffrage’s Big Three

While Cranford did not produce any suffragists of the stature of Stanton, Lucy, Anthony or Alice Paul, several locally prominent women took a very visible pro-suffrage stance.

Fannie Bates: A September 29, 1912 San Francisco Call article entitled “Cranford, N.J., Ruled by Women Like Its Fiction Prototype” focused on Fannie Bates. It claimed that she had driven a beer bottling plant out of town and forced the closing of several gambling clubs (addressing some of the women’s issues raised in the 1848 Seneca Falls convention.)

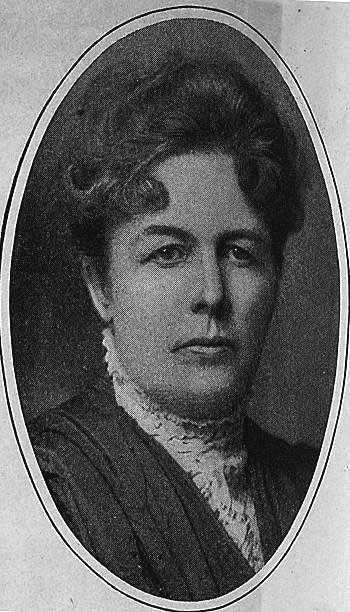

Fannie Bates – 1890

Bates founded the Village Improvement Association from among members of the Wednesday Morning Club, and VIA drove movements to clean up the town, plow the streets of snow, build a town library and improve schools. Newspaper articles from that time report on numerous Suffrage-related events held at Bates’ Hampton Hall boarding house.

Elizabeth Miller Bates: Fannie Bates’ daughter-in-law Elizabeth Miller Bates’ eye-opening moment came as follows. “I was a watcher at the polls when an illiterate drunk appeared and put his ‘X’ on the ballot. It made my blood boil to think that I could not vote and he could. It seemed so unfair. I couldn’t vote and yet I thought I could make a better decision than he”. (The Chronicle, 2/15/1995.)

Elizabeth Miller Bates

After visiting one of her sisters in Illinois, where women had been enfranchised in 1913, Elizabeth joined the Equal Franchise League in Cranford and was their representative at a Trenton hearing for women’s suffrage. In 1914, even though she could not vote herself, she was elected to the Board of Education and served for thirteen years. She continued an active life of community service right up to her death at age 101.

Alice Lakey: Was a nationally recognized crusader in the Pure Food Movement. In 1905 through the General Federation of Women’s Clubs, Lakey encouraged over one million women to write letters in support of pure food legislation. The Pure Food and Drug Act was enacted the following year. She followed that with seeking protection for milk and helped establish the Pure Food League.

Alice Lakey

In addition to being a nationally recognized food and drug crusader, Alice Lakey was also a no nonsense suffragist.

When several local political candidates scoffed at being asked to make known their position on suffrage, Alice wrote the following letter to the editor published in the May 7, 1914 Cranford Citizen:

The question has been asked why the Equal Franchise League included the names of local candidates for office at the coming election in sending out their letter of enquiry as to the position of candidates on the question of Votes for Women.

It will be recalled that one local candidate stated in his reply that his opinion on the question was of comparatively little consequence, another that the question was irrelevant. …

Men opposed to suffrage for women or even indifferent to it are too apt to agree with the public spirited Rochester politician Dr. Goler told us of in 1907. When asked to vote for a certain measure that would ensure clean milk for the Rochester babies, the lover of humanity said ‘What good will that do, babies ain’t got no votes.’

The woman has no vote – yet, that is why The Equal Franchise League would like to see elected to local offices men who will support their work in every instance for the betterment of Cranford

Alice Lakey

President

Equal Franchise League

Others Also Served in the Trenches

In addition to Fannie Bates, several other local women frequently hosted events, most often for the Equal Franchise League. Mrs. R. D. Thonsend of Holly Street (first names of married women were never given) hosted teas, and a presentation “New Jersey Next – the Bridge” for, and the 1915 annual meeting of, the local Equal Franchise League chapter.

Mrs. N. K. Thompson was selected chair of the Nominating Committee for the 1916 Elizabeth New Jersey Suffrage Convention. In 1918 she was Press Committee Chair for the local Equal Franchise Committee chapter, and also hosted 40 women in her home for a presentation by Miss Ethel Ogden on the recent enfranchisement success in New York.

Final Thoughts

While Cranford produced no suffragists of national stature, Women’s Suffrage was clearly an issue important to many Cranford women (and some of its men). They actively followed national events and conducted countless local activities in support of Women’s Suffrage an effort that was ultimately successful. We have much to thank them for.

Sources:

- Cranford Chronicle, various

- Cranford Citizen, various

- Gupta, Alisha Haridasani, “The Suffragists Fought to Redefine Femininity. The Debate Isn’t Over”, The New York Times, 8/26/2020

- Pecinger, Julie, “Worth Repeating … Fannie Bates ‘Mother of Cranford’”, Cranford Historical Society, “The Mill Wheel”, Holiday 2009

- Pecinger, Julie, “Elizabeth Bates: Suffragist to Civic Leader”, Cranford Historical Society, The Mill Wheel”, Winter 2020

- “Cranford, N.J., Ruled by Women Like its Fiction Prototype”, The San Francisco Call, Vol. 112, No. 121, 9/29/1912

- www.history.com/topics/womens-rghts/seneca-fall-convention

- www.history.com/this-day-in-history/cpmgress-passes-the-19th-amendment

- www.nationalgeographic.org.article/woman-suffrage

- www.nps.gov/articles/voting-rights-in-nj-before-the-15th-and-19th.htm

- Weiss, Elaine The Women’s Hour: The Great Fight to Win the Vote, Viking, 2018

Recent Comments